Many barrels of ink have been spilled in management literature over defining what exactly constitutes a team. From the many we reviewed, we found two common themes:

- The focus on a common goal or purpose

- Being defined by what they do, as opposed to what they are.

What’s missing is the definition of what a team is—that covers teams that are high-performing, low-performing, and everywhere in between, and withholds judgment about what a team should be or aspire to. We also need a definition that recognizes teams are made up of relationships—and that people can belong to multiple teams.

So, here is our Core Strengths definition:

Let’s break that down.

A team is a relationship …

Actually, a team is a network of several relationships.

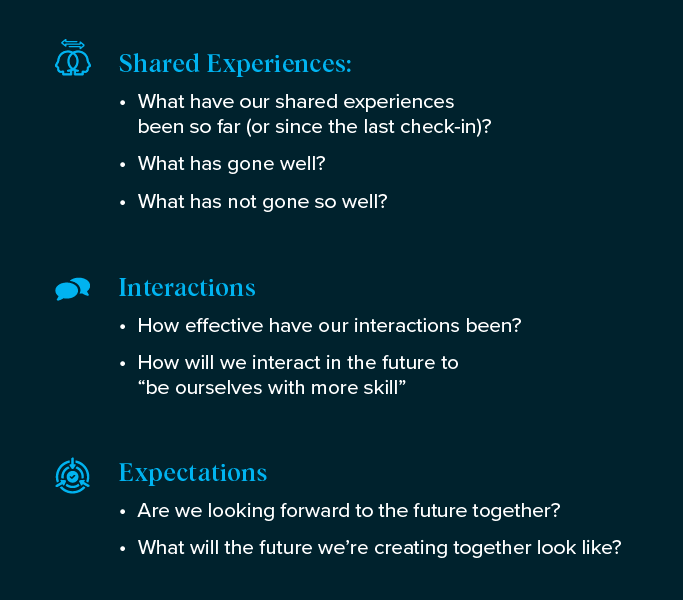

A relationship is a connection built on a foundation of shared experiences, interactions, and expectations. A team is usually formed because a pursuit requires more than one person’s efforts, and that is the basis for the shared expectations. The interactions that happen in day-to-day work become shared experiences.

For example, when a new member is hired into a project team of seven (making it a team of eight), seven new one-to-one relationships are added to the team, along with all eight people’s expectations about how the new member will fit in and what they will do in the future.

Assuming the new role was well defined and communicated, all eight people should share expectations, but this is not always the case. I’ve worked with several teams who welcomed new members, only to find that multiple people’s expectations were grossly misaligned—creating a frustrating experience for new members from day one.

Because teams are made of relationships, it’s important to merge new people into a team in the right way: they must be a good fit for the team and add a new perspective, and the hiring manager must manage their unconscious biases when recruiting. And it’s important to remember that you can never exactly reproduce the person who left and the team dynamics with them—for better and for worse.

A regular (e.g., quarterly) team relationship reset

This exercise is crucial when the team makeup changes. But even if nobody is joining or leaving the team, it’s important to pause once in a while and take stock of shared experiences and expectations. If the relationship is strong and trusting, then the team can deliver together.

… between two or more people …

In sports and work, it only takes two, at minimum, to make a team.

Arguably the most successful rugby team of all time, the New Zealand All Blacks, has thirty-six members, only fifteen of whom can be on the pitch during play. The All Blacks would also say that their team includes many more than the playing squad, including coaches, management, and support staff, who all have a critical role to play.

Many times, success isn’t found on the teams that are made of the best X number of individual players, but in groups who genuinely believe they are a team and respect the importance of everyone’s role, whether that role is in the spotlight or behind the scenes.

… who have an interest in the results …

An interest means you are affected by the results—win, lose, or draw. That means sharing the rewards for achieving shared goals, but also sharing the consequences of poor performance.

An interest can also mean passion or commitment, which may make team members more willing to set aside their personal interests in service of a shared goal. And the reverse is true: if one person is lethargic or actively disengaged, it’s a drag on the whole group. We’ve all been on teams where people are not passionate about what they’re doing, or don’t care about the shared purpose, yet still combine their efforts for financial gain or other reasons.

Team members can be passionate about results without being passionate about the cause—that’s realistic and okay.

… of their combined efforts.

Ideally, combined efforts mean collaboration. But many teams do not actually collaborate. Members of some sales teams, for example, have individual goals and incentives and do their work solo. But even if they don’t collaborate, they still have an interest in the results of their combined efforts; they get an extra bonus based on the team’s collective results.

But even if you work individually, it’s useful to understand what everyone else contributes. You can be more helpful to your colleagues if you know what they do, and vice versa.

If you build it, will they team?

Building a team could mean forming a completely new team, adding members to an existing team, or improving the capabilities of current team members. Regardless of the situation, team building means developing relationships within the team.

While ropes courses and escape rooms can be a fun shared experience, the value is not in the ropes or the room. The value is in seeing how the team interacts outside the workplace, then applying those insights to their workplace interactions.

Before you get into the offsite activity, I suggest starting team building with a conversation about the team’s purpose, values, and goals, then connecting those larger reasons for existing to the relationships within the team.

You can use the following discussion guide whether you are starting a new team or leading one with a long history. In a small team, this can be an open conversation. If you have a large team, it can be more useful to split into subgroups for discussion, and then bring the whole team together. As a leader, you can either facilitate yourself or bring in an outside facilitator, so you can be fully immersed in the content instead of guiding the process.

Download our guide to team building.

Then, during the offsite activity, weave in the themes that the group discussed during the preparatory conversation. Team members will already be thinking about those topics, so they will likely come up naturally as they move through the activities.

“We did it ourselves!”

Teams are relationships. As a team leader, you will have a relationship with each member of the team, but team member’s relationships with each other need to be more important than their relationship with you—or you risk creating a problematic environment where people look primarily to you for guidance and decisions.

This can be tough for a leader because you may worry it will put you out of a job. But your job as a leader is not to solve everyone’s problems, it’s to think about strategy and how to raise the bar, then empower the team to come up with solutions.

You can develop your team to succeed as a group in this way by encouraging relationships between team members. This is where taking time to establish a clear philosophy will pay big dividends. A clear philosophy that defines the purpose, values, goals, and stakeholders can serve as a compass for team members to navigate their work and make their own decisions. It defines the desired results of their combined efforts, so they can decide which course of action will further the goal.

Download our guide to team building.

Once you’ve defined the philosophy, get into the habit of reviewing recent performance with these questions:

- How does that align with our purpose?

- How well did we live up to our values?

- How did it contribute to our defined goals?

- How did it affect our stakeholders?

Soon, everyone on the team will start asking themselves these questions automatically. Before you know it, they will consistently make decisions that advance the team’s cause, even during times of uncertainty. They’ll feel empowered and take personal accountability. They will feel—because it’s true—that they did it themselves.