We have one word in the English language to describe everything from declining a meeting because you’re already booked to violence between two hostile nations: conflict.

In this context, as we talk about differences of opinion and clashes of personality at work, we use opposition to describe an objective disagreement and conflict to describe a more emotional experience in which people feel threatened or at risk.

Most conflicts involve some elements of opposition, and opposition can grow to become conflict when people feel threatened. This is why so many organizations are concerned about creating an environment of psychological safety. If people don’t feel safe to voice their opinions—or worse, are attacked for doing so—interpersonal conflict can quickly set in and it becomes difficult to deal objectively with opposition.

When everyone feels valued, though, we can productively engage in opposition—and we should welcome it. Opposition can be a source of creativity and innovation.

When conflict isn’t resolved, though, relationships—and therefore teams and organizations—pay a high price. The most obvious costs are associated with employees leaving the organization. But poor strategic decisions, lackluster implementation, and missed opportunities resulting from conflict can be more costly than turnover. Investing time in interpersonal conflict and resolving it well creates an asset; it clarifies issues, drives productive changes, and builds relationships that last.

This blog discusses the skills you can build to anticipate what’s likely to trigger conflict, prevent yourself and others from tipping over from opposition into conflict, identify when you are heading into conflict, manage existing conflict effectively, and resolve a conflict. These are not easy skills that you’ll master after reading one blog. The good news is that you can build these skills through practice in real-world workplace scenarios.. Your career and organization will be better for it.

Anticipate what is likely to trigger conflict for yourself and others.

Conflict is a sign that something is important to us. As civil rights activist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “The ultimate measure of a [person] is not where [they stand] in moments of comfort and convenience, but where [they stand] at times of challenge and controversy.”

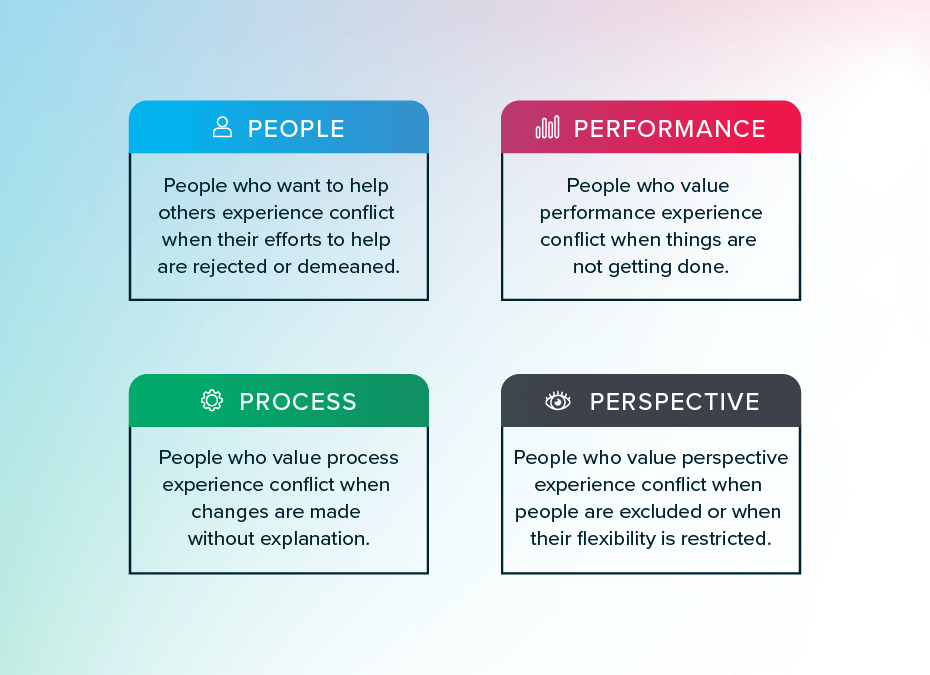

People care deeply about different things and thus have different conflict triggers:

Note that all of the above examples are things left unsaid or undone; conflict isn’t always triggered by an action. And most of the time, conflict is triggered unintentionally. Someone who values performance might compliment someone who wants to help people on their high sales numbers, and the person who wants to help people will feel that their most important contribution is totally invisible.

In addition, people often think they’re avoiding conflict when they say nothing, but all avoidance does is turn healthy opposition into conflict and make the problem worse.

Action:

- Get to know who you are and what is likely to trigger conflict for you. And get to know the people you work with and what is likely to trigger conflict for them. You can only achieve this by spending time getting to know each other, asking questions to be curious and listening with the intent to understand and learn about each other.

Core Strengths can help with this.

- Think about your preferred communication style and your colleagues’, and tweak the delivery of your message in a way that resonates for them (see section 4). “I’ve been looking at this months financial results and the amount of clients you have helped has been remarkable.”

Read this blog for a primer on building this skillset.

Prevent yourself and others from going into conflict.

The key here is to try hard not to offend others and to try even harder not to be offended.

Conflict triggers usually happen because of a misunderstanding about the intent of the conversation, the words used, or the communication style.

Often when we’re passionate about a subject, we’ll excitedly raise our voice, or talk over others. If someone does that, what story are you telling yourself? If “They’re talking over me” turns into “They’re so arrogant” which turns into “They don’t value my opinion,” recognize that those are assumptions on your part, not fact.

Action:

- Consider your current relationship with each of your colleagues. If you have had bad experiences with them in the past, reflect on those, question the stories you’ve been telling yourself, and replace them with facts. (Challenge Assumptions- Add Information – Exchange Perspectives).

- Enter the conversation assuming the best in yourself and the others involved. Look for the positive intentions behind their previous behavior and the stories they may be telling themselves. Recognize that you are worthy and capable of having this conversation; you deserve to be in the room.

Identify when you and others are going into conflict

We have all been surprised by conflict or by someone’s unexpected reaction, so you might be surprised to learn that conflict can be predictable.

There are patterns of changes in focus that everyone follows, and those patterns are part of your personality. If you’ve already completed the SDI 2.0, you will have read about your conflict sequence, which explains how your motives change in a predictable and sequential manner as conflict starts and as it gets worse.

- In the first stage, you focus on yourself, the problem, and the other people involved.

- The second stage is when other people’s needs go out of focus and all you see is yourself and your view of the problem.

- In stage three, even the problem can go out of focus as you make a final stand or just walk away from it all (self-preservation).

To learn more about individual conflict sequences, read this blog.

Our best chance of resolving a conflict is at stage one. The key is to be able to spot the behavior differences in ourselves and others as quickly as possible.

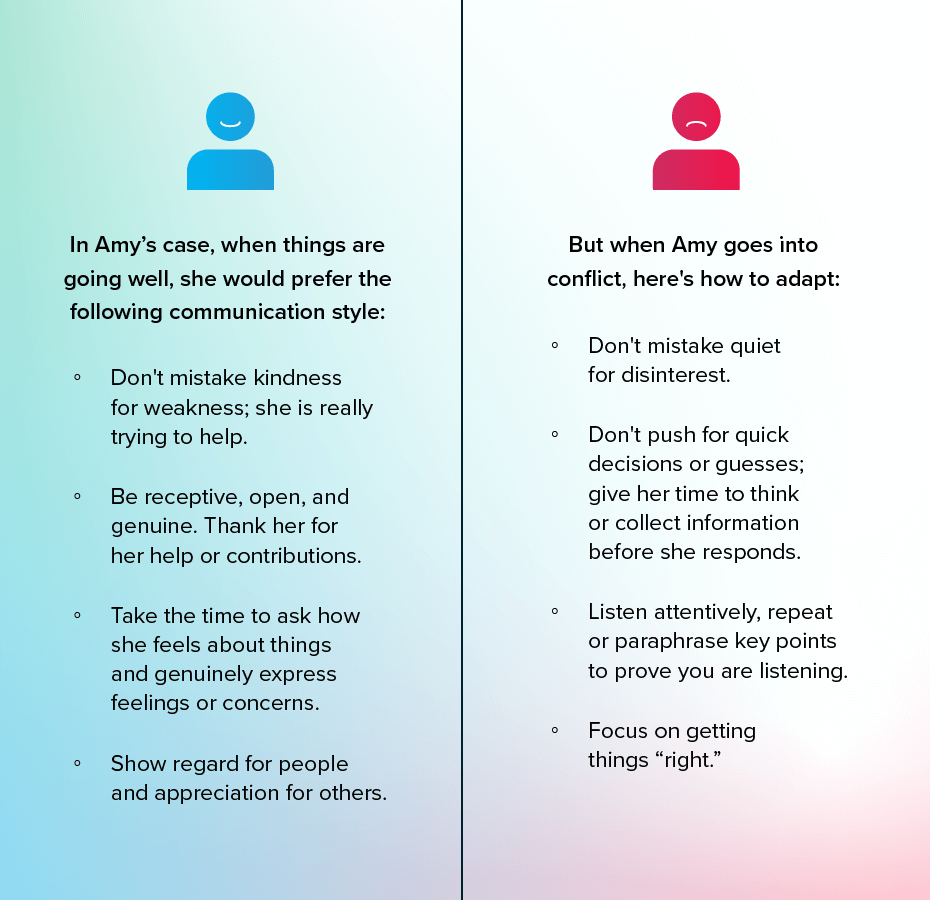

Some people will get quieter or ask more questions as they seek to resolve what is bothering them. Others will press for a quick resolution and others may start to accommodate more than usual. For example, Amy is normally very approachable but doesn’t appear to be as warm as she normally is. That could be a clue that something is bothering Amy.

We can sometimes have a blind spot when someone’s conflict response looks like our normal state or their change in behavior is hard to spot.

You know trust exists in the relationship when the person in conflict can speak up and say, “You probably haven’t spotted this, but X is really bothering me.” Anytime someone is vulnerable enough to do that, it’s a gift to the colleagues and team, giving others permission to do the same.

Action:

- Get to know the conflict sequence of each of your colleagues and the subtle changes in behavior that tell you something is wrong.

- Think about your own behavioral indicators for when something is bothering you and how others might observe it. If you’re unsure, ask your closest colleagues, family, and friends.

Manage conflict in yourself and others.

Even with the best prevention skills, sometimes conflict happens. We often need to communicate differently with people when they are in conflict than when things are going well for them.

The key in any conflict situation is to be able to step into the other person’s shoes and try and see the situation from their perspective, then to behave in a way that will get them back to their best version of themselves.

Action:

Get to know and understand how to communicate with others when things are bothering them, and adapt your style to meet the current situation.

Resolve the conflict and check where the relationship is now

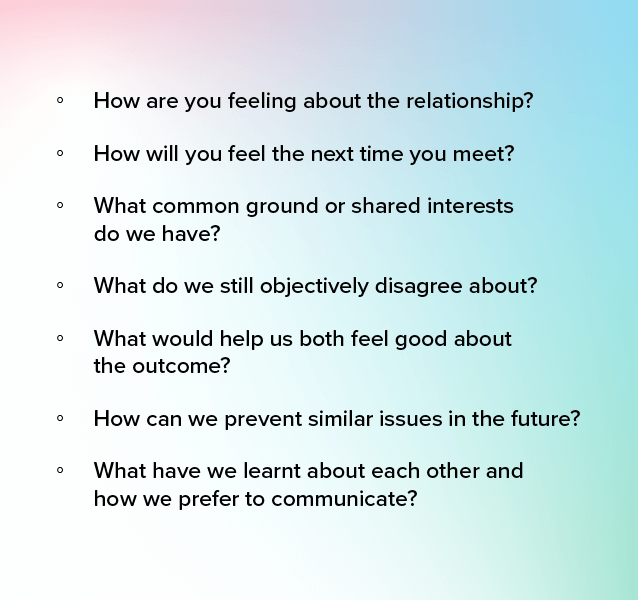

Sometimes, we think we’ve resolved the conflict, when we have simply just resolved today’s issue.

Many times, when someone tells me they have resolved a conflict I ask how they feel when they see the other person. Too often, they answer that they still feel uncomfortable with the other person and don’t contact them as much anymore.

Accumulated, unresolved conflict can feel a bit like excess baggage— undesirable and too heavy to carry around. You will enter the next conversation with the other person already in a state of conflict. This is not a productive way to continue a relationship.

If the issue is heavy, take a break at a certain point in the conversation (perhaps after you’ve resolved today’s issue but not released all the baggage), get a good night’s sleep, and consider processing your side of it with a trusted confidante.

But don’t use this break to avoid resolution. You have to return to the conversation and resolve the underlying conflict by talking about the relationship and how you’ll avoid conflict in the future. It is also good to explain why you need the break and your intent is to be in a better position to resolve the issue.

Action:

Check yourself after a situation or issue has been resolved. Consider the following questions:

Preventing all conflict is an aspirational, but unrealistic, goal. In any relationship, people are motivated in different ways, have different values, and want different results. Those personalities and priorities are going to bump into each other, so we should welcome opposition and not be surprised when sometimes opposition turns into conflict.

The key is to manage the experience of conflict, so you can work through your differences productively. In the absence of any clear common ground, you can always start with a shared goal of wanting to preserve the relationship. If that’s true for both parties, then reconciliation is in sight.

Remember, effective communication is a skill that takes practice. By approaching conflicts with an open mind and a willingness to find common ground, you increase the chances of reaching a positive resolution.

Contact Core Strengths for help with conflict management on your team.